In the last two posts I described growing up on 70-acre piece of land that my parents converted from barren hills surrounded by swamps into complex farm fields, and a vibrant lake. I said it sounds idyllic, and in many ways it was. The gifts I received from my parents in the first eighteen years of my life are the foundation of a sense of fulfillment and happiness that I know is very great.

But life on the farm was a mixed blessing.

The very gifts with which our family grew up created, I think, a kind of exceptionalism in each of us. We were the place where our classmates came to swim and ice skate and picnic. We were a preeminent family in our parish. Once a week, the Maryknoll brothers studying in the novitiate in Akron came to swim, work on the farm, picnic, or sled down the snowy-laden hills with us. My father was a leading lawyer in the city, and his best friend, Father Basil, who was a professor of history at a university in Cleveland, spent every Saturday afternoon and shared evening dinner with us, where we inevitably listened to high-level discussions of current ethical, philosophical, or theological questions. At school, if any of us of whatever age said “Father Basil says…”, the nuns inevitably acquiesced. We always had the upper hand on that one.

These experiences and so many like them gave us a sense of confidence and identity. But it also gave us a false sense that we were right. Like our big house on the hill, we stood above others. Yes, we had responsibilities and obligations, which profoundly shaped the decisions we made about our lives and futures.

But we weren’t always as right as we thought we were. And our Right Answer assumptions often led us to presenting our views with an unappealing self-righteous arrogance. And interestingly, a lack of creativity. We had the right answers. We didn’t have to search for solutions.

But we weren’t always as right as we thought we were. And our Right Answer assumptions often led us to presenting our views with an unappealing self-righteous arrogance. And interestingly, a lack of creativity. We had the right answers. We didn’t have to search for solutions.

It also left us with somewhat limited social skills. We didn’t really know how even our school friends lived. They spent more time in our house than we did in theirs. Even today, many of us agree that we find it extremely difficult to make small talk. Yes, we can enter into in-depth discussions about the meaning of life, death, the existence of God, abortion, the poor, racism, and politics. But we are a deadly serious lot. Most of us have had to learn from our life’s partners that very few people are quite as eager to endure our endless debates as we are.

Life on the farm also left us, especially the girls, unusually naive. That wasn’t only a result of the protective isolation of living on the farm (which perhaps by now I should begin calling an “estate,” rather than a farm). It was in part due to the times and the Catholic religious culture we lived in. We learned to be supportive and to some extent even subservient to men, but we did not learn how and when we had the right to say No. Consequently, as adolescents and young adults we got ourselves into sexual encounters that we misread. We felt betrayed and angry at unspoken promises we felt had been made, and which, from a more mature perspective, obviously had not been offered.

Unfortunately, our idyllic life on the farm came to a crashing end with the death of my mother of cancer at the age of 48. Eight months earlier I had entered the convent, and my mother, who knew she had only weeks to live, made it clear to me that I had a calling from God, and that I was not to come back home to care for my eight younger brothers and sisters, the youngest of whom was 7. My mother also, I am sure, agreed with my father that he would marry the women we all called “Aunt Mary.” She had been married to my mother’s brother who had also been my father’s law partner until his death 5 years earlier. She and my father married four months after my mother’s death.

That’s when everything changed. My father directed that everyone still living at home should address her as “mother,” but she was not a mother they recognized or felt loved by. We always refer to the time after my mother died as “The Second Regime.”

As children we were never told we were growing up on a Dorothy Day farm. After Dad died and we discovered their correspondence, it had little value to us and the letters were destroyed. Because neither the joys of the first Regime with Mom, or the pain and the anguish of the Second Regime are due principally to the fact that we were living on a farm. They are due far more to the love and generosity, to the limits and tragedies, of those individuals living there.

As Communism has demonstrated most recently, utopia does not exist independently in the system. Right now, we see today in countries throughout the world, including the United States and Britain, no system in itself operates independently of the people who are living within it. As Thomas Jefferson said, freedom is something we must work constantly to protect. The same is true of love. The system can’t do it for us.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/shropshirestar.mna/ZYWCGSWD65E7TMBPZZQ3FZBG3M.jpg)

When I was ironing recently, the electric cord on my steam iron suddenly caught fire, sending a burning flame along the side of my hand that had been holding the iron. I managed to pull the cord from the wall, and thankfully, wearing short sleeves, put the flame out before it caught my clothes on fire. It did burn my hand along about 2 inches, leaving me with an appreciation that being burned alive was emphatically not an easy way to go.

When I was ironing recently, the electric cord on my steam iron suddenly caught fire, sending a burning flame along the side of my hand that had been holding the iron. I managed to pull the cord from the wall, and thankfully, wearing short sleeves, put the flame out before it caught my clothes on fire. It did burn my hand along about 2 inches, leaving me with an appreciation that being burned alive was emphatically not an easy way to go.

Not all problems are solvable, of course. But the attitude we take toward living with them can be Quacking with the Ducks. Or Soaring with the Eagle.

Not all problems are solvable, of course. But the attitude we take toward living with them can be Quacking with the Ducks. Or Soaring with the Eagle. The first is to pause after reading a challenging article and to summarize for myself what I read. For instance, right now economists are rethinking economic theory in the light of changes occurring as the result of global trade and increasingly sophisticated computerization of data. Last night I read an article and then spent ten minutes writing mental notes clarifying for myself issues that in the past I might have dismissed as either not important or too difficult for me to bother with. Exactly how quantitative easing replaces lowering interest rates to stimulate a country’s economy and why this approach is increasingly needed is now quite clear to me. The October 12, 2019 edition of

The first is to pause after reading a challenging article and to summarize for myself what I read. For instance, right now economists are rethinking economic theory in the light of changes occurring as the result of global trade and increasingly sophisticated computerization of data. Last night I read an article and then spent ten minutes writing mental notes clarifying for myself issues that in the past I might have dismissed as either not important or too difficult for me to bother with. Exactly how quantitative easing replaces lowering interest rates to stimulate a country’s economy and why this approach is increasingly needed is now quite clear to me. The October 12, 2019 edition of

Five hours later I began to worry that the entire family were gone for the weekend. Boudica began to suspect the same thing and was making a lot of noise about being trapped in a berry patch for so long. She did try out the strawberries, but they were not to her taste.

Five hours later I began to worry that the entire family were gone for the weekend. Boudica began to suspect the same thing and was making a lot of noise about being trapped in a berry patch for so long. She did try out the strawberries, but they were not to her taste.

Belief in God, on the other hand, is based on faith, which by definition is NOT based on evidence. It is often a deeply held conviction that shapes our lives, our choices, our deepest values, but cannot be proved.

Belief in God, on the other hand, is based on faith, which by definition is NOT based on evidence. It is often a deeply held conviction that shapes our lives, our choices, our deepest values, but cannot be proved.

I have been surprised at the scope and depth of responses to my last post discussing what Pope Francis should do about the problem of pedophilia and other sexual misconduct among supposedly celibate priests. Most of the responses have come to me privately, almost all of them with deep feeling.

I have been surprised at the scope and depth of responses to my last post discussing what Pope Francis should do about the problem of pedophilia and other sexual misconduct among supposedly celibate priests. Most of the responses have come to me privately, almost all of them with deep feeling.

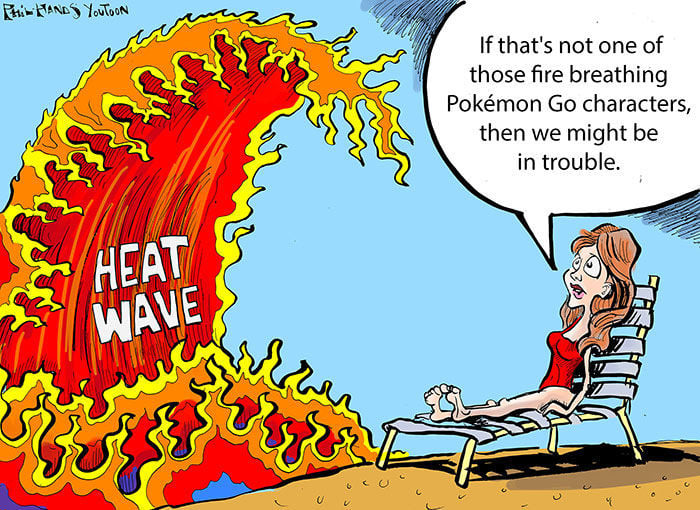

Well, we don’t have great slabs of ice, so I experimented with freezing a 5-quart container and putting it in front of a fan in our bedroom. Before the ice had melted, the temperature in the room was reduced by 2 degrees to 88. And it did provide a slightly cooler breeze for several hours.

Well, we don’t have great slabs of ice, so I experimented with freezing a 5-quart container and putting it in front of a fan in our bedroom. Before the ice had melted, the temperature in the room was reduced by 2 degrees to 88. And it did provide a slightly cooler breeze for several hours.

If you were given the same grammatical schooling I was around the age of ten, you might be cringing at a sentence like “Who is the bell tolling for?” To be classically correct, I should be saying “For whom is the bell tolling?”, not mixing up the correct use of the words who and whom, and adding to the mess by ending the sentence with a preposition.

If you were given the same grammatical schooling I was around the age of ten, you might be cringing at a sentence like “Who is the bell tolling for?” To be classically correct, I should be saying “For whom is the bell tolling?”, not mixing up the correct use of the words who and whom, and adding to the mess by ending the sentence with a preposition.

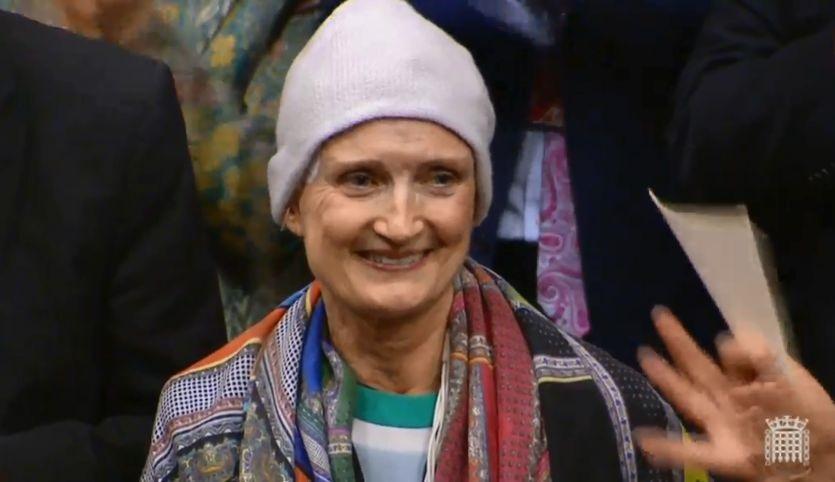

In several of my Life as a Nun posts on this blog, I have described my experiences as an attractive, intelligent, and above all incredibly naive 27-year old emerging from convent life to the “real world” of hippie New York City. I am remembering what I learned during those days as I try to understand the “Me too’ism” unleashed by the galley of allegations of sexual abuse against Hollywood’s Harvey Weinstein. It is hitting the headlines here in England, displacing terrorism, Brexit, and many other international events of global significance. Already a highly placed political figure in Parliament and cabinet has been displaced, and accusations of many others are rampant, some potentially serious, many unsubstantiated.

In several of my Life as a Nun posts on this blog, I have described my experiences as an attractive, intelligent, and above all incredibly naive 27-year old emerging from convent life to the “real world” of hippie New York City. I am remembering what I learned during those days as I try to understand the “Me too’ism” unleashed by the galley of allegations of sexual abuse against Hollywood’s Harvey Weinstein. It is hitting the headlines here in England, displacing terrorism, Brexit, and many other international events of global significance. Already a highly placed political figure in Parliament and cabinet has been displaced, and accusations of many others are rampant, some potentially serious, many unsubstantiated. I see now that sexual abuse and misunderstandings are often a two-way street. Learning to send and also to read signals from members of the opposite sex is not simple. A pat on the knee, an arm around the shoulder, a particular facial expression may or may not be a come-on. How close people are physically, whether sitting or standing, is particularly cultural. Both men and women may deliberately or unconsciously, send signals through the clothes we wear, the way we walk, our behavior when we are in a bar or disco. And the meaning of those signals often changes in the context within which they occur.

I see now that sexual abuse and misunderstandings are often a two-way street. Learning to send and also to read signals from members of the opposite sex is not simple. A pat on the knee, an arm around the shoulder, a particular facial expression may or may not be a come-on. How close people are physically, whether sitting or standing, is particularly cultural. Both men and women may deliberately or unconsciously, send signals through the clothes we wear, the way we walk, our behavior when we are in a bar or disco. And the meaning of those signals often changes in the context within which they occur.

But we weren’t always as right as we thought we were. And our Right Answer assumptions often led us to presenting our views with an unappealing self-righteous arrogance. And interestingly, a lack of creativity. We had the right answers. We didn’t have to search for solutions.

But we weren’t always as right as we thought we were. And our Right Answer assumptions often led us to presenting our views with an unappealing self-righteous arrogance. And interestingly, a lack of creativity. We had the right answers. We didn’t have to search for solutions.

This need to belong, she believes, is the evolutionary source of all religion. It would explain why we sometimes cling to our religious identity in the face of overwhelmingly contradictory evidence. We will die for this right to belong. And as both history and contemporary events unfortunately demonstrate, we will not only die for it. We will kill for it. We are born with a need to belong, and to be deprived of this essential need leaves us devastated, disoriented, even destroyed.

This need to belong, she believes, is the evolutionary source of all religion. It would explain why we sometimes cling to our religious identity in the face of overwhelmingly contradictory evidence. We will die for this right to belong. And as both history and contemporary events unfortunately demonstrate, we will not only die for it. We will kill for it. We are born with a need to belong, and to be deprived of this essential need leaves us devastated, disoriented, even destroyed. The Romans held up the honeybee as one of the most admirable of all living organisms. They work as a group for the good of the whole, not simply for their own individual well-being whatever happens to every other bee. Not only that, but the work of the bee actually adds values to the plants it pollinates and from which it extracts its own life-sustaining nutrients.

The Romans held up the honeybee as one of the most admirable of all living organisms. They work as a group for the good of the whole, not simply for their own individual well-being whatever happens to every other bee. Not only that, but the work of the bee actually adds values to the plants it pollinates and from which it extracts its own life-sustaining nutrients. I’m beginning to sound like a broken record to myself. I keep reaching the conclusion that, for better or for worse, we’re all in this together.

I’m beginning to sound like a broken record to myself. I keep reaching the conclusion that, for better or for worse, we’re all in this together.

Why, you might ask, am I writing about such an inane event?

Why, you might ask, am I writing about such an inane event?

Parents are repeatedly advised these days to make sure their children are not becoming addicted to the internet, unable to tear themselves away to get healthy exercise and face-to-face conversation with real people. Another problem is the “sound-bite” approach to learning, which limits children’s ability to learn to follow complex arguments through to the finish. The temptation is to read the headlines and think you know the whole story.

Parents are repeatedly advised these days to make sure their children are not becoming addicted to the internet, unable to tear themselves away to get healthy exercise and face-to-face conversation with real people. Another problem is the “sound-bite” approach to learning, which limits children’s ability to learn to follow complex arguments through to the finish. The temptation is to read the headlines and think you know the whole story. First of all, more than ever it’s necessary for me to remember that I am not all-knowing and infallible. I obviously make assessment and decisions and try to live by my values. But I need to remember that I might be wrong. Even very wrong. On things that are little. But also about things that might be very big.

First of all, more than ever it’s necessary for me to remember that I am not all-knowing and infallible. I obviously make assessment and decisions and try to live by my values. But I need to remember that I might be wrong. Even very wrong. On things that are little. But also about things that might be very big.

I have the feeling that the changes that are taking place in my own life keep galloping ahead in the same way that the world is changing. On the one hand, I feel such a small part of our globalized world, and at the same time as I listen to the world news, it feels like a mirror of my own life these days.

I have the feeling that the changes that are taking place in my own life keep galloping ahead in the same way that the world is changing. On the one hand, I feel such a small part of our globalized world, and at the same time as I listen to the world news, it feels like a mirror of my own life these days.

.JPG)

Here’s an example. China was accepted into the World Trading Organization in 1993, it looked like an unalloyed win-win situation for the world. It indeed has been a win for Chinese workers who now supply 20% of world-wide manufacturing exports. China has been transformed from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions out of poverty. And in the developed world, the less well-off benefited hugely from cheaper imports of everything from computers to solar panels.

Here’s an example. China was accepted into the World Trading Organization in 1993, it looked like an unalloyed win-win situation for the world. It indeed has been a win for Chinese workers who now supply 20% of world-wide manufacturing exports. China has been transformed from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions out of poverty. And in the developed world, the less well-off benefited hugely from cheaper imports of everything from computers to solar panels.